When you live with chronic pain, it’s natural to be cautious about exercise as you don’t want to worsen your pain. But the truth is, avoiding exercise is doing the opposite of protecting yourself. Being active and exercising really does help your chronic pain, with studies and industry bodies labeling it as “the miracle cure we’ve all been waiting for.”

- Benefits of exercise for chronic pain

- 1.1 – Strengthens muscles

- 1.2 – Reduces stiffness

- 1.3 – Helps to maintain general health

- 1.4 – Good for mental health

- 1.5 – Reduces cognitive issues

- 1.6 – Reduces stress levels

- 1.7 – Retrains the brain

- 1.8 – Builds confidence

- 1.9 – Decreases inflammation

- 1.10 – Increases immune function

- 1.11 – Increases energy and decreases fatigue

- 1.12 – Helps with sleep

- 1.13 – Reduces pain and increases functioning

- How to start exercising

- Yoga exercise routines to try now (videos)

Benefits of exercise for chronic pain

-

Strengthens muscles

When you avoid exercise for a long period of time, deconditioning occurs, which means that your muscles weaken because they are not being used. So when you do try to be active, you feel more pain because your body is not physically fit.

Doing regular exercise keeps muscles strong and readies your body for the demands of day-to-day life. Even when we look at osteoarthritis where the joint may have worn down, having strong muscles around that joint makes you more mobile and supports the weakened joint more effectively.

-

Reduces stiffness

When you stay in one position for a long time, your body stiffens up; this is an even more present problem when it comes to chronic pain conditions. Being regularly active can reduce this stiffness and make movement easier.

-

Helps to maintain general health

Doing regular exercise helps to keep your body healthy and maintains regular functioning, whether you have chronic pain or not. Exercise reduces the risk of illnesses like diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure and so much more; this in turn reduces the risk of you developing comorbid health conditions.

Exercise can also help you lose or maintain your weight. When you’re overweight there is more pressure being put on the joints and muscles in your body, basically overworking them, and this can increase your pain and worsen other health conditions. Obesity has also been found to increase the risk of some types of chronic pain even without taking into account the amount of weight being carried as explained here, “obesity has also been associated with an increased risk of hand OA (Osteoarthritis) and neuropathic pain, which are usually thought to be unrelated to the weight load on the musculoskeletal system.”

-

Good for mental health

During exercise, chemicals called endorphins are released and sent around your body through your bloodstream as explained in this study. Endorphins trigger a feeling of positivity and wellbeing within the brain, making you feel good; this in turn boosts your mood.

Often when you’re struggling with mental illness, which so often comes hand in hand with chronic pain, your levels of a hormone called serotonin can be low. Exercise is understood to increase levels of serotonin and therefore can help to stabilize your mood. This study explains that, “motor activity increases the firing rates of serotonin neurons, and this results in increased release and synthesis of serotonin”

Exercise can also be grounding and distracting which can really help with both pain and anxiety. As you focus on the activity you’re doing, your breathing and how your body is moving, you can get into a meditative flow state, feeling grounded in the present moment.

-

Reduces cognitive issues

Exercise gets blood pumping to the brain to aid it in functioning optimally, as well as strengthening the nerve connections in the brain. It also increases the size of the hippocampus which is the part of the brain which controls memories, therefore making you more likely to retain short term and long-term memory as explained in this study.

-

Reduces stress levels

Engaging in regular exercise actively reduces levels of cortisol, otherwise known as the stress hormone, in your body, allowing you to feel more relaxed. Higher intensity exercises, when you are ready for them, can have a greater impact on reduction of cortisol, as explained here. Exercise also helps to maintain the right levels of adrenaline, which is the hormone that gets you ready for ‘fight or flight’, and so keeps you calmer.

-

Retrains the brain

Fear avoidance often develops in those with chronic pain. They begin to fear movement and therefore avoid activity and exercise; this contributes to the pain cycle. With regular gentle exercise, built up in a gradual way, you are tackling fear avoidance and retraining your brain, teaching it that exercise does not need to be feared. This study explains how this is an important part of exercise therapy for chronic pain patients, “therapists should try to decrease the anticipated danger (threat level) of the exercises by challenging the nature of, and reasoning behind their fears, assuring the safety of the exercises, and increasing confidence in a successful accomplishment of the exercise.”

-

Builds confidence

As you start to engage in exercise and realise that you can do it and that it doesn’t need to be feared it can truly do wonders for your confidence. This increases not only your confidence that you can exercise despite chronic pain, but also your general sense of self-esteem, knowing that you are doing all you can to make your body as healthy as it can be.

-

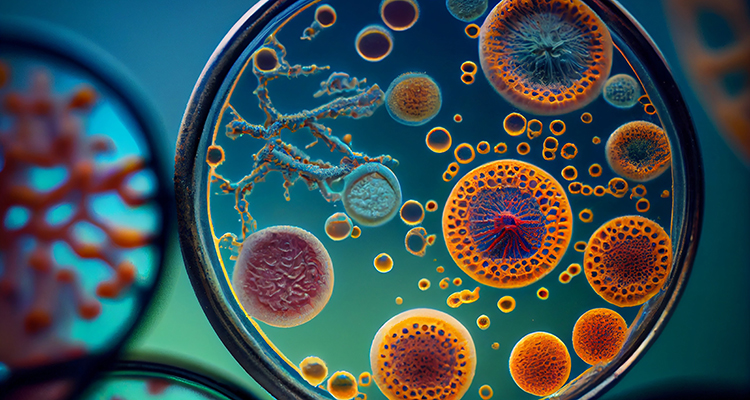

Decreases inflammation

Doing regular gentle exercise produces an anti-inflammatory response; it literally tackles inflammation and lowers the inflammatory response that is so often triggered with many chronic pain conditions. This study explains that, “Decreased inflammatory responses during acute exercise may protect against chronic conditions with low-grade inflammation.”

-

Increases immune function

With some chronic conditions, immune responses can be low making patients more susceptible to viruses and infections. Regular exercise helps to keep the immune system functioning properly. This study explains that, “regular general exercise also reduces susceptibility to viral and bacterial infections, suggesting that there are mechanisms at play that improves the overall immune function.”

Pathways Helps You Break The Pain/Fear Cycle

Enjoy any one of our hundreds of meditations

-

Increases energy and decreases fatigue

When you’re fatigued it can feel like the last thing you want to do is start exercising, but moderate exercise reduces fatigue and increases your energy. This study found that when people first start to exercise they can, “increase their energy levels by 20 percent and decrease their fatigue by 65 percent by engaging in regular, low intensity exercise”

As you start to exercise the blood flow around your body increases, distributing more oxygen and nutrients, providing your muscles with the fuel they need to produce energy. Exercise also helps your central nervous system to increase energy in your body and fight fatigue as explained here.

-

Helps with sleep

Exercising during the day tires your body out in a healthy way, so that at night you are more likely to sleep soundly despite your pain. It won’t be an instant cure, but the more you are active during the day, the more your body will be ready for sleep.

-

Reduces pain and increases functioning

Although the exact mechanisms behind it are yet to be understood, regular exercise produces an analgesic effect, which means that exercise is directly reducing pain! This study explains, “for those suffering from chronic pain, exercise can also have a pain-relieving effect. There is a substantial and growing body of evidence that long-term exercise training can provide pain relief across many different chronic pain conditions”

As you begin to feel less fatigued, to gain confidence in moving your body and to feel healthier in general, your levels of daily functioning can improve. You can start to replace maladaptive behaviours with adaptive ones, such as being more social, eating in a healthier way and feeling more in control of your life.

How to start exercising

It’s important that you start exercising in the right way; jumping right in from not engaging in any exercise to doing extreme workouts is going to be detrimental to your body, while building up your exercise in a gradual way will be immensely helpful for your mind and body.

Pain neuroscience education

The first step is getting educated about how chronic pain works, whether through therapy or self-education; it’s about learning that exercise is not going to damage your body and that you don’t need to fear it. Acute pain is a warning system for our body, so when you feel pain it’s natural that you take notice; however, chronic pain is a faulty alarm system, meaning that the pain you are feeling is not indicating damage.

Learning about this first gives you the confidence and peace of mind when you start engaging in exercise that you are safe and that you don’t need to fear the movements you are doing, even if you are in pain. This study states that, “musculoskeletal therapists can alter pain memories in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, by integrating pain neuroscience education with exercise interventions.”

Pacing

It can be easy to try to ‘make the most’ of low pain days, but this can cause what is known as the boom bust cycle. This means that you actually end up causing a flare and worsening your symptoms by trying to do too much. Pacing yourself can prevent the boom bust cycle. Start building up your exercise slowly, working on doing light exercises such as walking or swimming, and gradually building up the time and distance.

Self awareness

As you start to exercise you will learn what works for you and what causes a flare. You’ll start to become much more aware of your body. It’s about finding that sweet spot that allows you to push yourself productively, but not push yourself too far. When you live with chronic pain your symptoms vary almost constantly so this can be a tough balance to strike. It can take time and is often trial and error, so remember not to be too hard on yourself.

Remember that you are in control. You can decide what is too much and what you can push through. You don’t need to compare yourself to others, or to push yourself too hard because you feel you ‘should’ be able to do something. At the same time, it’s important to keep that motivation up to continue doing your best.

Some questions to ask yourself before you begin exercising are shown below. These questions can help you to assess whether you should exercise or rest. They can aid you in determining whether you can do the activity as you planned, or whether you may need to scale back that activity to fit your symptoms (for example shortening the distance you plan to walk). After you’ve assessed your symptoms, you may decide you need to take someone with you to support you, or you may need to utilize some of your management techniques to enable you to continue with the planned exercise.

- Are you in pain right now?

- How much pain are you in?

- How fatigued are you currently?

- Realistically could you exercise through the pain?

- Would you be at risk for injury/flare if you exercised now?

- What do I have planned for the rest of the day/tomorrow which could be affected if I flare?

Using a pain scale to rate your pain levels can be a great way to keep track of them, for example answering the question ‘how much pain you are in’ with a number out of 10. Keeping a journal of your exercise progress can help you to become self aware. For example, if one day you decide to push through pain that you rated 6/10, and that caused you to flare for a few days, you’ll know that next time you should try scaling back your exercise if your pain is above a 6.

Choosing a low impact exercise

Low impact exercise refers to exercise which doesn’t put too much pressure on your joints. They’re less strenuous than other exercises and are great for those with health conditions or people just getting started with exercise.

Examples of low impact exercise include:

- Walking

- Cycling

- Swimming

- Strengthening and stretching exercises

- Tai Chi

- Pilates

- Yoga

There’s a lot of choice which means you can find something you actually enjoy. Finding the exercise you engage in fun is going to help you to keep pushing forward despite your symptoms.

Getting help

You don’t have to start exercising on your own, in fact for the best results and to ensure that you are approaching exercise in the best way for you, it can be a great idea to get help.

Exercise based therapies can help you to figure out your tolerance level, helping you to build up exercise without inducing a pain flare; this study found that, “Exercise therapy has found to be beneficial in CP (chronic pain), but it should be appropriately and individually tailored with emphasis on prevention of symptom flares and applying adequate recovery strategies.”

A lot of therapies to tackle chronic pain will incorporate exercise and movement; this article explains the help that a therapist can provide: “By addressing patients’ perceptions about exercises, therapists should try to decrease the anticipated danger (threat level) of the exercises by challenging the nature of, and reasoning behind their fears, assuring the safety of the exercises, and increasing confidence in a successful accomplishment of the exercise.”

You could try cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), graded exposure therapy or pacing. You can access this sort of help through your doctor, a specialist, a private therapist, an occupational therapist, a physiotherapist or online through an app like Pathways Pain Relief (update Aug 2023: Pathways is now a web app! Start our program here).

Yoga exercise routines to get you started

Yoga allows you to have the benefits of exercise combined with mindfulness. This manageable routine helps to tackle lower back pain and release muscle tension. Gentle guidance throughout helps you to perform the movements safely and with reassurance. You’re able to adjust the movements to suit your own abilities.

The following five minute routine is focused around energizing your body and mind. It’s a great one to do in the morning to prepare you for the day ahead! The routine incorporates seven basic body movements to provide a strengthening yet gentle exercise routine.

Pathways Helps You Break The Pain/Fear Cycle

Enjoy any one of our hundreds of meditations

References

- Science News, (2008), “Low-intensity Exercise Reduces Fatigue Symptoms By 65 Percent, Study Finds”

- Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, Volume 61, Pages 60-68, Stoyan Dimitrova, laine Hultenga, Suzi Honga (2017), “Inflammation and exercise: Inhibition of monocytic intracellular TNF production by acute exercise via β2-adrenergic activation”

- Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, Simon N Young, (2007), “How to increase serotonin in the human brain without drugs”

- The Journal of Pain, Volume 20, Issue 11, Pages 1249–1266, David Rice, Jo Nijs Eva Kosel, Timothy Wideman, et al (2019), “Exercise-Induced Hypoalgesia in Pain-Free and Chronic Pain Populations: State of the Art and Future Directions”

- British Journal of Sports Medicine, Smith BE, Hendrick P, Bateman M, et al (2019), “Musculoskeletal pain and exercise—challenging existing paradigms and introducing new”

- Practical Pain Management, Volume 16, Issue 9, Kelly M. Naugle, PhD., (2017), “Role of Physical Activity in Managing Chronic Pain in Older Adults”

- Current Pain and Headache Reports, Volume 11, Issue 2, pp 93–97, Martin D. Hoffman, Debi Rufi Hoffman, (2007), “Does aerobic exercise improve pain perception and mood? A review of the evidence related to healthy and chronic pain subjects”

- Manual Therapy, Volume 20, Issue 1, Pages 216-220, Jo Nijs, Enrique Lluch Girbes, Mari Lundberg et al (2015), “Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories”

- The Clinical Journal of Pain, Volume 31 , Issue 2, p 108–114, Daenen, Liesbeth PhD, PT., Varkey, Emma RPT, PhD., Kellmann, Michael PhD., Nijs, Jo PhD, PT (2015), “Exercise, Not to Exercise, or How to Exercise in Patients With Chronic Pain? Applying Science to Practice”

- Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, Dean E. Jacks, James Sowash, John Anning, Thomas McGloughlin, Fredrick Andres, (2002), “Effect of Exercise at Three Exercise Intensities on Salivary Cortisol”

- PNAS, Kirk I. Erickson, Michelle W. Voss, Ruchika Shaurya Prakash, et al (2011), “Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory”

Please note: This article is made available for educational purposes only, not to provide personal medical advice.